Of Elephants and the birds — Trinity vs. Unity

Of Elephants and the Birds – Trinity vs. Unity[1]

In or around 570 A.D., Abrahah, the Ethiopian governor of Yemen, a Christian, attacked Makkah. His army included elephants, and by some accounts only one elephant, which were never seen before in Hejaz, a specter that left an everlasting imprint on the Arab memory. On the outskirts of Makkah, Abrahah’s plans were foiled by a ‘heavenly’ intervention in which an obviously un-opposable army was destroyed. Surah Fil (–elephant) refers to this event. In the same year Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was born.

The manner in which said Surah is translated and explained in various exegeses, creates an absurd scenario. Instead of reading the purpose of the Quran which draws attention to the survival of Abrahamic monotheism despite the overwhelming attacks on it, primarily by Christianity, legends are drawn in which flocks of birds appeared over Abrahah’s army and pelted the troops with stones that the birds carried in their beaks till the whole army perished. The closest that one can get to the purpose of the birds in the Surah is that flocks of birds converged on the dead and dying and probably were eating the carrion of dead bodies by pelting them against stones to tear the flesh or the dead had skin manifestation of a pestilence that struck the troops and appeared as if the dead were pelted by small pebbles and they died from small in size but numerous blows. The Surah reads as follows:

105:2. Did He not (cause the war to end in confusion and) ruin their plan (to destroy Ka`bah by making it revert on themselves)?

105:3. And He sent against them flocks of birds,

105:4. (Which tore off flesh from their bodies to eat by) striking them against [also Arabic: ‘bi’ – with] stones of hardened and petrified clay.

105:5. And thus He reduced them to rotten chaff (and in a similar way will they be ruined who would ever make an attack to destroy Ka`bah).[2]

A simple point missed by the readers is that the plan of Abrahah’s army is ruined first (verse 105:2) due to an outbreak in its midst before the flocks of birds, probably vultures, arrive on the scene (verse 105:3) for scavenging (verse 105:4). The term – flocks of birds, in no way implies birds in a flight alone. It is a common scene of vultures huddled together as a flock on a carcass. Since there were many carcasses, hence the plural – flocks. The whole event over the period of time has become the source of many legends. If the Surah is plainly read, there is no cause and effect of arrival of birds and ruining of Abrahah’s plans against Ka`bah, rather it is vice versa. Mention of the birds is only in the context of an exemplary end of a now helpless body of aggressors whose malicious plan, against all odds, had already been foiled. Simply put, what the birds did was the final nail in the coffin of a disgrace meted out to an apparently mighty and invincible. The aspect which got imprinted on the memories were the presence of the elephant(s) in the invading army and the flocks of birds converging on the hapless troops.

Of note is that this Surah was revealed in Makkah as a solace to the Prophet when he was facing not only a colossal opposition but an incessant persecution. Its assurance is not only for the Prophet, but also for the Muslims after him. The Surah prophesies that despite the attacks of the mighty and powerful of any faith on Islam, it will survive and thrive, as it has in the past and so will it in the future – Have you not considered how your Lord dealt with the People of the Elephant? Did He not ruin their plan?

Even though Quran is not a book of history, it is always in step with the logic of history. Consequently, it leaves no room for legends to emanate from its lines, but Quran has no control over the legends that emanate from the minds themselves. Such minds, then try to find validation for their preconceived ideas from a fragmented reading of the Quran. Such twisted logic then attributes to and interjects into Quran fanciful ‘pre-established’ conclusions. A classic and oft repeated case of reading conjectures ‘into’ Quran, rather than reading plain facts ‘from’ Quran.

This event as explained in its details in Ethiopian sources is as follows:

Outbreak of an epidemic in Abrahah’s army in the vicinity of Makkah was not a novelty. In the Encyclopedia of Pestilence Pandemics and Plagues[4] one finds that the epidemic outbreaks in and around Makkah have been a common occurrences, some of which are excerpted as follows:

Disease on Campaign – … Debilitating diseases did not have to kill combatants to cripple an army; they could simply take so many off active duty as to blunt its effective force….In the later sixth century CE, the Christian Ethiopian prince Abraha (r. c. 525–553) controlled a considerable portion of the Arabia Peninsula. The prince’s military campaign to convert Arabians to Christianity in 569–571 was halted abruptly when smallpox or measles broke out among his troops as they approached the important trading center of Mecca. So weakened were the Ethiopians that they lost what they had controlled in Arabia, an event celebrated in the Koran’s Sura 105. Had Mecca been converted, the life story of Muhammad (579–632), Prophet of Islam, might have been very different… [page 759]

Returning Troops and Refugees –There are many cases in the historical record of armies or military units returning home and bringing with them diseases of all kinds (– venereal diseases). As troops are demobilized, they spread their diseases deep into the population of their home states…In 570 Byzantine troops on campaign near Mecca (Saudi Arabia) contracted a similar disease and, upon return, spread it about the eastern Mediterranean. [page 761]

In the spring of 1831, pilgrims traveling through Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula brought cholera to Mecca during the annual hajj. In three weeks, almost 3,000 pilgrims perished returning to their homes—a situation that would repeat itself throughout the nineteenth century. [page 99]

In 1845 cholera broke out again in Bengal with a bidirectional projection towards

Arabia in 1846 (Aden and Djeddah), arriving in Mecca in November, Mesopotamia (Baghdad, September 1846) and at the coast of the Black Sea (Tibilissi, July 1847). [page 100]

The worst pilgrimage outbreak ever in Mecca during 1865 marked the fourth pandemic when 15,000 of the estimated 90,000 pilgrims died. [page 106]

The fifth pandemic arrived in Mecca from India’s Punjab in 1881 and struck again the following year. Once again, the toll was terrible, estimated at over 30,000 dead among 200,000 pilgrims. [page 108]

Smallpox, too, which is easily transmitted by fomites, is another classic disease of pilgrimage. In the 1930s, an outbreak in Africa was traced to pilgrims, and the last major epidemic in Europe was carried to Yugoslavia by a pilgrim who had contracted it in Mecca. Meningococcal meningitis, which is not only highly contagious but also provokes a carrier rate as high as 11 percent, has been carried to America, Africa, and Asia by returning pilgrims. Less contagious diseases such as tuberculosis, Dengue, and poliomyelitis have also had documented mini-epidemics traced to the gathering and then dispersal of pilgrims. Upper respiratory illnesses are particularly efficiently spread in this way. For instance, while in Mecca, 40 percent of pilgrims get some sort of viral upper respiratory illness, [page 481]

Neisseria meningitides is a pathogen that has long caused seasonal epidemics of meningitis in parts of Africa: the so-called “meningitis belt.” The disease has recently spread more widely. Studies with molecular markers have shown how Muslim pilgrims who brought an epidemic strain of N. meningitides from southern Asia to Mecca in 1987 then passed it on to pilgrims from Sub-Saharan Africa—who, after returning home, were the cause of strain-specific epidemic outbreaks in 1988 and 1989. [page 699]

In last two centuries alone, Makkah has been vulnerable to outbreaks of Cholera epidemics due to the people coming to its precincts from afar:

In November 1846, cholera struck Mecca, killing over 15,000 people in and around the city.[5] Some 4,000 Muslim pilgrims were estimated to have died in Mecca in 1902. (Mecca has been called a “relay station” for cholera in its progress from East to West; 27 epidemics were recorded during pilgrimages from the 19th century to 1930, and more than 20,000 pilgrims died of cholera during the 1907–08 hajj.)[6]

Sir William Muir, a no friend of Islam, in his book “Life of Mahomet”[7] writes the following about Abrahah’s attack on Makkah:

The Viceroy of Yemen Invades Mecca A.D. 570.

In the year A. D. 570, or about eight years before the death of Abd al Muttalib, occurred the memorable invasion of Mecca by Abraha the Abyssinian viceroy of Yemen. This potentate had built at Sana a magnificent cathedral to which he sought to attract the worship of Arabia, and, thwarted in the attempt, he vented his displeasure in an attack on Mecca and its temple. Upon this enterprise he set out with a considerable army. In its train was an elephant;— a circumstance for Arabia so singular that the commander, his host, the invasion, and the year, are still called by the name of 'the Elephant.' Notwithstanding opposition from various Arab tribes, Abraha victoriously reached Taif; a city three days march east of Mecca. The men of Taif protested that they had no concern with the Mecca, and furnished the Abyssinians with a guide, who died on the way to Mecca, Centuries afterwards, men were wont to mark their abhorrence of the traitor by casting stones at his tomb as they passed.

And Threatens the Kaaba;

Abraha then sent forward a body of troops to scour the Tehama, and carry off what cattle they could find. They were successful in the raid, and among the plunder secured two hundred camels belonging to Abd al Muttalib. An embassy was despatched to the inhabitants of Mecca: 'Abraha,' the message ran, 'had no desire to do them injury. His only object was to demolish the Kaaba; that performed; he would retire without shedding the blood of any.' The citizens of Mecca had already resolved that it would be vain to oppose the invader by force of arms; but the destruction of the Kaaba they refused upon any terms to allow. At last the embassy prevailed on Abd al Muttalib and the other chiefs of Mecca, to repair to the viceroy's camp, and there plead their cause. Abd al Muttalib was treated with distinguished honour. To gain him over, Abraha restored his plundered camels but he could obtain from him no satisfactory answer regarding the Kaaba. The chiefs offered a third of the wealth of the Tehama if he would desist from his designs against their temple, but he refused. The negotiation was broken off, and the deputation returned to Mecca. The people, by the advice of Abd al Muttalib, made preparations for retiring in a body to the hills and defiles about the city on the day before the expected attack, As Abd al Matalib leaned upon the ring of the door of the Kaaba, he is said to have prayed to the Deity thus aloud: 'Defend, O Lord, thine own House, and suffer not the Cross to triumph over the Kaaba'. This done, he relaxed his hold, and, betaking himself with the rest to the neighbouring heights, watched what the end might be.

Is discomfited by pestilence.

Meanwhile a pestilential distemper had shown itself in the camp of the viceroy. It broke out with deadly pustules blains, and was probably an aggravated form of smallpox. In confusion and dismay the army commenced its retreat. Abandoned by their guides, they perished among the valleys, and a flood (such is the pious legend) sent by the wrath of Heaven swept multitudes into the sea. The pestilence alone is, however, adequate to the effects described. Scarcely any recovered who had once been smitten by it; and Abraha himself, a mass of malignant and putrid sores, died miserably on his return to Sana.

Muir, in the footnote to the paragraph above, then goes on to contextualize the historical events with the narrative of Surah Fil as follows:

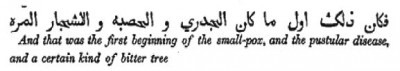

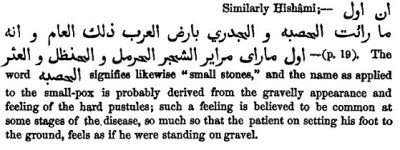

The accounts leave no room to question the nature of the disease having been a pestilential form of small-pox. Wackidi, after describing the calamity in the fanciful style of the Coran, add: 'And that was the first beginning of the small-pox.'[8] The word signifies 'small stones, ' and the name as applied to the small-pox is probably derived from the gravelly appearance and feeling of the hard pustules. The name, coupled with its derivation, probably gave rise to the poetical description of the event in the Coran: 'Hast thou not seen how thy Lord dealt with the army of the Elephant? Did he not cause their stratagem to miscarry? And he sent against them flocks of little birds which cast upon them small clay stones, and made them like unto the stubble of which the cattle have eaten.'

Historical records support that Abrahah’s army fell prey to an epidemic. His army had to march as a group for over six hundred miles from Yemen. The expedition itself made the troops prone to a contagion because of the close contact over an extended period. The long journey in the desert made the troops vulnerable to poor health and hygiene, both from limited rations of food and water, as well as, the exhaustion from travelling in a desert.

The summary scenario in light of Quran is in which flocks of birds, most likely vultures, gathered upon the dead and dying of Abrahah’s army. Quran only reports the vultures for their typical style of ripping the carrion in their feeding frenzy – (Which tore off flesh from their bodies to eat by) striking them against stones of hardened and petrified clay, and a despicable end to the transgressors – And thus He reduced them to rotten chaff. The dead of Abrahah’s army infested with the pustules of small-pox probably seemed to the onlookers as if smitten with small clay stones[9]. No matter how one translates the Surah, there is no mention of birds carrying pebbles in their beaks that they smote the army with.

Moral of the Surah is in its first two verses, which assure Divine protection of the Unity against the Trinity and an admonishment to the Trinity for its designs against the Unity.

[1] Attacks on Islam by Latter-Day — "Companions of the Elephant", by Imam Kalamazad Mohammed. Link: http://aaiil.org/text/articles/others/elephant.shtml

[2] Al-Fil – The Elephant: Nooruddin

[3]'Abraha fl. 6th century Orthodox Ethiopia – Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Link: http://www.dacb.org/stories/ethiopia/_abraha.html

[4] Encyclopedia of Pestilence Pandemics and Plagues, Edited by Joseph P. Byrne, volume I, A-M, Greenwood Press, Copyright © 2008 by Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

[5] Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846-63, UCLA School of Public Health. Link: http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/Snow/pandemic1846-63.html

[6] "Cholera (pathology): Seven pandemics". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Link: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/114078/cholera/253250/The-first-six-pandemics

[7] The Life of Mahomet, by William Muir LL.D., New Edition, Chapter III, p. xxvi-xxvii, Smith Elder & Co. 15 Waterloo Place, London, 1878.

[8] Footnote: Chapter Fourth – “The Forefathers of Mahomet, and History of Mecca, from the middle of the Fifth Century to the Birth of Mahomet 570 A.D”, p. cclxvi, The Life of Mahomet and History of Islam, To The Era of Hejira, by Sir William Muir, Esq. Vol I. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 65 Cornhill, 1858.

[Editorial note: al-jadree – the smallpox; al-hasba – the pustular disease (like small stones)]

[9] Footnote: Chapter Fourth – “The Forefathers of Mahomet, and History of Mecca, from the middle of the Fifth Century to the Birth of Mahomet 570 A.D”, p. cclxvi, The Life of Mahomet and History of Islam, To The Era of Hejira, by Sir William Muir, Esq. Vol I. London:

From T Ijaz:

My understanding is tayr or ‘birds’ can represent any biological vector flying through the air, so viruses like smallpox or measles may have lead to the deadly pandemic killing the army. Hurling stones at them may represent the disease symbolically, and in either case, the disease appeared as raised, pebbled skin