Showing Islam is Peaceful • Tolerant • Rational • Inspiring

| Home

|

| 1.

Islam |

| 2.

Ahmadiyya Movement Refuting the Qadiani Beliefs Khilafat in the Ahmadiyya Movement: Detailed article |

| 3.

Publications & Resources |

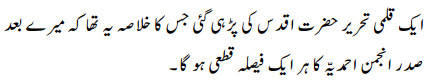

Anjuman made successor by the Promised MessiahIt was in his booklet entitled Al-Wasiyya (The Will), published about two and a half years before his death, that Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad announced the creation of the Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya, and formulated its main objectives, rules and regulations. He wrote:

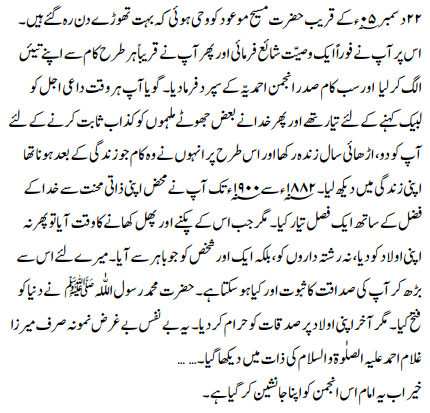

In an Appendix to Al-Wasiyya, the Promised Messiah published some rules and regulations of the Anjuman, from which we quote below as they show the position he gave to this body: “9. The Anjuman, which is to hold these funds, shall not be entitled to spend the monies for any purpose except the objects of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and among these objects the propagation of Islam shall have the highest priority.”Therefore the Anjuman was to be in control of all the finances and funds of the Ahmadiyya movement. It was to receive all the income of the movement and to determine how to spend it. “13. As the Anjuman is the successor to the Khalifa appointed by God, it must remain absolutely free of any kind of worldly taint.”Here the Promised Messiah calls the Anjuman as his successor. It is the Promised Messiah who is “the Khalifa appointed by God” and his successor is the Anjuman created by him. Rules and regulations of Sadr Anjuman AhmadiyyaIn February 1906, more comprehensive rules and regulations of the Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya, as approved by the Promised Messiah, were published in the Ahmadiyya community’s newspaper Badr. Go here to read some essential points from these rules. It is evident from these rules and regulations of the Anjuman, and the powers given to it, that the Promised Messiah established it as the supreme governing authority of the Ahmadiyya movement after him. There is no trace whatsoever in these rules of any system of personal khilafat or of any office of a khalifa having supreme authority over the movement. Therefore the Qadiani concept and system of khilafat is totally alien and opposed to the instructions of the Promised Messiah, and an utter negation of the system set up by him. Anjuman to be supreme after Promised Messiah’s lifeAbout a year later, it so happened that Mir Nasir Nawab, father-in-law of the Promised Messiah, opposed a certain decision of the Anjuman. When this disagreement was brought to the notice of the Promised Messiah, he wrote down the following verdict about the authority of the Anjuman, in his own hand-writing: “My view is that when the Anjuman reaches a decision in any matter, doing so by majority of opinion, that must be considered as right, and as absolute and binding. I would, however, like to add that in certain religious matters, which are connected with the particular objects of my advent, I should be kept informed. I am sure that this Anjuman would never act against my wishes, but this is written only by way of precaution, in case there is a matter in which God Almighty has some special purpose. This proviso applies only during my life. After that, the decision of the Anjuman in any matter shall be final.Go here to see this note in the Promised Messiah’s own hand-writing. This clear verdict of the Promised Messiah confirmed the Anjuman’s position as the supreme authority of the Ahmadiyya movement after his life-time, its decisions being final and binding. No individual head or khalifa was to have the power to set aside, revoke, or go against any decision of the Anjuman. Anjuman’s powers explained at the December 1908 annual gatheringThe note mentioned above was read out before the Ahmadiyya community at the December 1908 annual gathering (jalsa salana), the first one after the death of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. During this conference Maulana Muhammad Ali presented the report of the work of the Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya on the morning of 27th December 1908. At the end of his report, he read out this hand-written note of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. This was reported as follows in the Ahmadiyya community newspaper Badr:

After Maulana Muhammad Ali’s speech, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din addressed the gathering and spoke about the position of the Anjuman in the Movement. He said:

The gathering at which these speeches were delivered was the largest ever Ahmadiyya meeting up to that time. It was attended by the leading figures in the Ahmadiyya Movement including the head, Maulana Nur-ud-Din. Also present was Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad himself (who also gave an address) and others who were later prominent in the creation of the Qadiani group. This shows that it was a well known and publicised fact that the Anjuman had been designated by the Founder of the Movement as his successor for running the Movement. These speeches also show the sense in which Maulana Muhammad Ali and Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din accepted Maulana Nur-ud-Din as Khalifa. They regarded him as a head but who was within the system in which the Anjuman was the supreme executive body. This entirely refutes the Qadiani allegation that, by accepting Maulana Nur-ud-Din as Khalifa, the Lahore Ahmadiyya leaders had accepted the khilafat system. That khilafat system which the Qadianis mention, in which there is an autocratic the Khalifa possessing absolute, despotic power, was created by them after the Split of 1914. Maulana Nur-ud-Din’s exposition of Anjuman’s positionDuring his period as head, Maulana Nur-ud-Din too considered the Anjuman as being the khalifa of the Promised Messiah for governing the Movement. During the course of his khutba on the occasion of ‘Id-ul-Fitr on 16th October 1909, he re-iterated the position and the powers given to the Anjuman by the Promised Messiah. Referring to the booklet Al-Wasiyya, he said:

The following points emerge very plainly from this speech:

Mirza Mahmud Ahmad usurps Anjuman’s authorityThe establishment of the Anjuman on these principles by the Promised Messiah prevented anyone from becoming an autocratic head or creating an inherited spiritual seat (gaddi) in the Ahmadiyya Movement, as had been the fate of previous Muslim spiritual orders. Mirza Mahmud Ahmad, having exactly these ambitions of wielding absolute power, resented the formation and the powers of the Anjuman, and from the very time of the creation of the Anjuman he did all that he could to have it rendered powerless. In March 1914, Mirza Mahmud Ahmad was successful in his long-standing plans to gain the headship of the movement upon the death of Hazrat Maulana Nur-ud-Din. Immediately thereafter, having first ensured that no opposition could be voiced against him in Qadian, he had the following resolution of the Anjuman passed by his supporters:

By this resolution, Mirza Mahmud Ahmad removed from the Anjuman its position of supreme authority given to it by the Promised Messiah, and raised himself to the Divinely-appointed status of the Promised Messiah by writing his own name in Rule no. 18, giving his orders supremacy over the Anjuman’s decisions. He thus destroyed the system created by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, and replaced it by personal, autocratic rule by a khalifa, the concept of which is in complete violation of the principles of Islam as well as the teachings of the Promised Messiah. It will be seen that when Maulana Nur-ud-Din became head, he did not substitute his name for that of the Promised Messiah in this Rule. On the contrary, he followed the regulations laid down by the Promised Messiah regarding the powers of the Anjuman. Therefore, the sense in which M. Mahmud Ahmad made himself khalifa was entirely different from, and quite opposed to, the sense in which Maulana Nur-ud-Din was khalifa. This is one of the main reasons why those, like Maulana Muhammad Ali, who accepted Maulana Nur-ud-Din as khalifa could not accept M. Mahmud Ahmad as khalifa. Mirza Mahmud Ahmad’s 1925 speech: makes Anjuman entirely subservient to khalifaBy means of the change in the rules referred to above, Mirza Mahmud Ahmad arrogated himself to the position of an absolute leader whose orders had to be obeyed unquestioningly by everyone in the movement. Despite this amendment and despite the fact that the Anjuman now consisted entirely of his own supporters, he still felt insecure that the Anjuman might seek to regain its authority some time in the future. In a speech in October 1925, therefore, he laid down a new system of administration, reducing the Council of Trustees to an entirely subservient body. In this speech, published under the title Jama‘at Ahmadiyya ka jadid nizam ‘amal (‘A new system of working for the Ahmadiyya Movement’), at the very outset he attacked the principles upon which the Anjuman was founded, and declared:

He then announced his decision that the names Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya and Majlis-i Mu‘timidin (Council of Trustees) would be transferred to certain other bodies, so that their names would be retained but the institutions themselves would cease to exist! Mirza Mahmud Ahmad’s statement given above is self-contradictory and indeed plainly absurd. Firstly, he admits that the Promised Messiah had given his approval of the name and the rules of the Anjuman, but he says that these were “devised by others” and then attacks the rules. This amounts to alleging that the Promised Messiah approved these rules merely at the behest of “others”, without himself knowing or caring that these would be harmful to the Movement, and now Mirza Mahmud Ahmad was going to rectify the Promised Messiah’s error! Secondly, since in his view the names as well as the rules were “devised by others” and merely approved by the Promised Messiah, it is entirely illogical for him to retain the names because of their association with the Promised Messiah’s time but destroy the rules. The rules were also from the Promised Messiah’s time. Therefore, the names and the rules should both be eliminated or both be retained! M. Mahmud Ahmad’s admissions in his speechThere are several very interesting and revealing admissions made by Mirza Mahmud Ahmad in this speech. He said:

Here Mirza Mahmud Ahmad has made the following admissions:

“For the sake of the khilafat we had to make an unparalleled sacrifice. And that was that we sacrificed for its sake the old followers of the Promised Messiah, those who were called his friends, those who had a very close relationship with him. If this religious difference had not arisen between them and ourselves, they would be dearer to us than our own children because they included those who knew the Promised Messiah and those who were his companions, and had worked with him. … But because a difference arose regarding a teaching which was from God, and which had to be accepted for the sake of our faith and the Jama‘at, we sacrificed those who were dearer to us than our children. So, over this question, we have made such a magnificent sacrifice that no other sacrifice can equal it. This is far greater than sacrificing one’s life because in that case a man sacrifices only himself. But here we had to sacrifice a part of our Movement. “If even after so much sacrifice the movement still remains insecure, that is, it is at the mercy of a few men who can, if they so wish, allow the system of khilafat to continue in existence, and if they do not so wish, it cannot remain in existence, this cannot be tolerated under any circumstances. Because the institution of khilafat was not included in the basic principles of the Jama‘at, the movement lives in the constant danger which can turn pledged members into non-pledged members, and by the stroke of the pen of ten or eleven men Qadian can at once become Lahore. Here Mirza Mahmud Ahmad has made the following interesting admissions:

Mirza Mahmud Ahmad makes Anjuman totally powerlessMirza Mahmud Ahmad then went on to announce in this speech that in his new system the term Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya would refer to “the khalifa and his advisors”, the advisors would advise and the khalifa would decide, and this would be known as the decision of the Sadr Anjuman. The Majlis-i Mu‘timidin (Council of Trustees) would merely carry out the decision without question. It can be seen that these institutions, which had been created by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, were demolished by Mirza Mahmud Ahmad in order to create a system of absolute, autocratic, personal rule, and establish a family succession. |